Utopia as Ideology: 'The Years of Rice and Salt' (Kim Stanley Robinson, 2002)

A review of The Years of Rice and Salt, by Kim Stanley Robinson (2002)

What if, instead of killing off a third of Europe’s population, the Black Death killed 99%? How would the great civilizations of Islam, China, and India cooperate and compete absent European dominance? And how would history unfold without the rise of the West? This is the world Kim Stanley Robinson’s alternative history explores.

To cover these vast periods of time, the novel follows three souls as they are repeatedly reincarnated throughout history—each archetypal, but evolving through the cycles of Saṃsāra. They are, at various times Mongol warriors, slaves, eunuchs, wild beasts and nuclear physicists, to name a few of the forms they take.

Though this narrative device is interesting, some of their cycles felt flat. Often nothing but thin canvases for KSRs characteristic digressions into scientific inquiry—though these in of themselves can be quite engrossing. As I said in my review of The Deluge, novels covering such vast subjects seem to struggle to marry human and historical narratives. The Years of Rice and Salt is no exception.

Yet just as the cycle of Saṃsāra acts as a device to travel through history, this structure also acts as a platform to explore KSRs political philosophy. His unashamed Utopianism is expressed in much of his other work (such as the Mars Trilogy, or more recently in The Ministry for the Future) and usually has a whiggish teleology that leads indelibly from barbarism to enlightenment.

Though this is also more or less true in The Years of Rice and Salt, I think its ultimate message about Utopia is much more nuanced. Rather than ‘progress’, as a process towards utopia, it is better conceived of as an ideology. A set of interrelated beliefs and practices that can crop up and disappear throughout history—Utopia is the unified framework, but progress is the (often non-linear) manifestation of its elements.

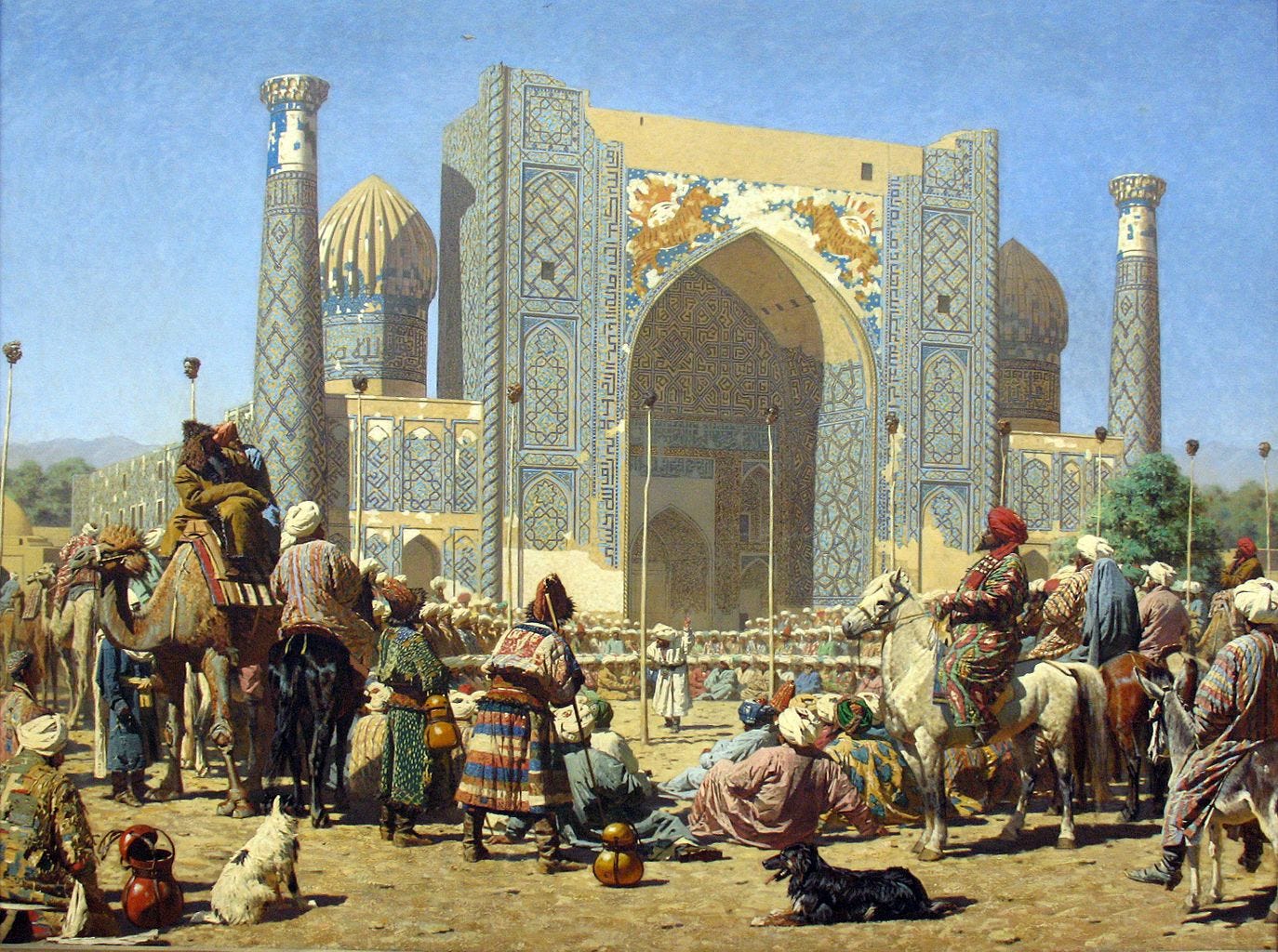

Elements of progress appear and wink out constantly throughout The Years of Rice and Salt. Zheng He’s great treasure fleet brings connectivity to the world, before being burnt in an isolationist policy turn. An egalitarian Taifa is established in the Muslim recolonization of Europe, but snuffed out by fundamentalist warlords. A scientific renaissance in Samarkand is cut short by plague. A Multicultural and technological renaissance leads to a devastating world war that costs a billion lives.

Each Saṃsāran iteration of this utopian ideology brings refinement, evolution, and losses of knowledge. Progress in this novel is not linear but swirls amongst other currents, till the correct conditions allow it to bubble to the surface. This depiction of Utopianism is a grounded one with an ambiguous optimism. There is no inevitably to progress, but neither can it ever truly be defeated. It is, much like the protagonists of The Years of Rice and Salt, forever being born anew.

-Ben Shread-Hewitt